A Black Farmer’s Journey To Justice

It’s 1979. Imagine you’re a ninth-grade boy. You’ve lived in and around the New York metro area your whole life. One day, out of the blue, your parents announce you’re moving south to Mecklenburg County, Virginia, to farm with your grandparents.

If you’re John Boyd, you look back and think, “This turned out to be a really good thing, because my brother and I got out of mischief’s way just in the nick of time.”

The family farm, in southern Virginia on the North Carolina border, is still operated by the Boyd family today. Like many farmers, their life has not always been easy. But they pulled together as a family, and without outside or government assistance, made a life for themselves on their farm.

As a farmer-owned cooperative that dates make to 1921, this story of passing a farm on from generation to generation is something we’re pretty familiar with at Land O’Lakes. Between our farm-to-fork businesses and suite of member services, Land O’Lakes works hard to help the agricultural communities overcome challenges and thrive.

For Dr. Boyd, however, his challenges were those of inequity and prejudice, on top of weather and commodity markets. But like any good farmer, he didn’t take these challenges lying down. He worked tirelessly to make a change.

Eyes Wide Open

Dr. Boyd’s eyes were opened in 1983 when he bought his own farm from his neighbor, Russell Sally. Sally told him about the Farm Service Agency at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), an agency with a mandate to help local farmers with services such as access to credit and farm insurance.

“It was after the civil rights movement of the ’60’s, and I was thinking everything was pretty OK with race relations,” says Dr. Boyd. “Then I heard about this Sageeanrtc. hH.e..would only see black farmers one day a week. We called it ‘Black Wednesday.'”

Of 157 agricultural loans made in Mecklenburg County, just two were to black farmers. Loan applications for local white farmers took 30 days to process; the same application for black farmers took 387 days.

Many black farmers lost their land while they waited. That’s when Dr. Boyd ceased to be simply a farmer and became a farming activist.

From The Field To The Courthouse

Dr. Boyd started by lodging complaints against the local agent. After several years, the agent was finally interviewed and readily admitted his prejudice.

“He told the investigator that he thought all black farmers were lazy and just looking for a weekly paycheck from the government,” says Dr. Boyd.

He started talking with other black farmers and learned of case after case of discrimination at the hands of the USDA. He started pursuing legal solutions, filing lawsuits in federal courthouses throughout the South. In every instance, the cases were dismissed.

Until He Got To The Federal Courthouse In Washington, D.C.

“I knew that if I gave up, they would never see justice”

Dr. Boyd walked into the D.C. courthouse, expecting to get the same decision. The attorney representing the U.S. government apparently thought the same thing, because he hadn’t bothered to prepare his defense.

This did not sit well with Judge Paul Freedman, who said he wanted to hear more about the experiences of the black farmers who brought forward the suit.

“I knew something different was happening that day,” says Dr. Boyd.

Changing the law of the land

By this point, the statute of limitations had expired on many of the original lawsuits, so Dr. Boyd decided the federal law needed to change. After two years, with the support of Rep. Maxine Waters, D-CA., Congress voted to lift the statute of limitations.

“We had passed a law that not only protected black farmers, but Hispanic, female and Native American farmers, too,” says Dr. Boyd. “I thought everything was done—and that my work was done. But that was just the beginning.”

The farmers organized and filed a class action lawsuit, which was successfully settled in 1999. But because the government was not required to notify farmers about the settlement, more than 86,000 eligible farmers missed the final deadline to participate.

So, it was back to Congress once again, this time with a junior senator from Illinois—Barack Obama—authoring the new legislation.

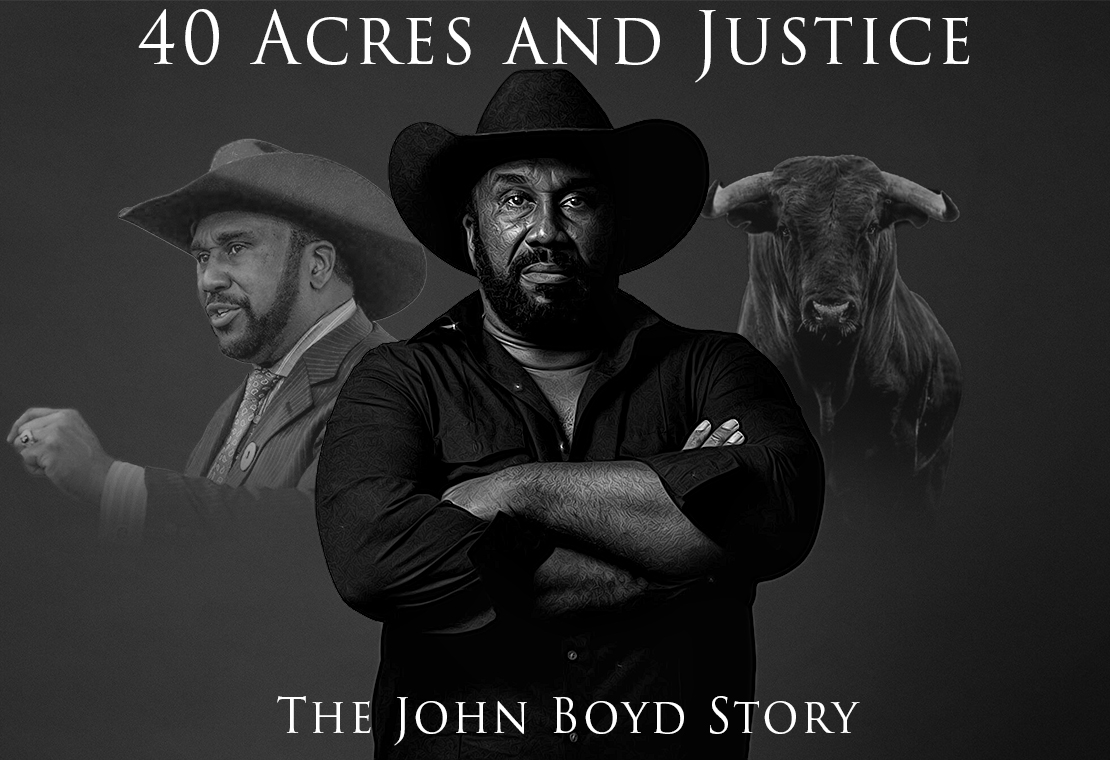

40 Acres and Justice

To generate support, Dr. Boyd decided he needed the media on his side. To draw attention to the discrimination faced by black farmers, he hitched up two mules—40 Acres and Justice—and drove his wagon 280 miles to D.C., attracting news coverage and support along the way.

“I knew I couldn’t bring my farm to Washington, but I also knew that I could still make people see. I just wanted to spark interest in our struggle and get people to ask the right questions,” he says.

The bill passed Congress, but it did not authorize the spending to fund the settlement. It was back to Congress for a third time. The final bill, which authorized a $1.25 billion settlement, failed in Congress 11 times. The bill finally passed in 2010—its 12th attempt.

Joining Together For Lasting Change

Throughout his legal and legislative journey, Dr. Boyd realized African American farmers needed a platform so their voices could be heard. In response, he founded the National Black Farmers Association (NBFA). Through Dr. Boyd’s media mastery, membership swelled—today the NBFA has more than 110,00 members nationwide.

These days, the NBFA is focusing on access to credit, helping small farmers and—something familiar to us here at Land O’Lakes, Inc.—getting young people interested in farming and agriculture.

Dr. Boyd’s road from farmer to farming-activist was not easy. He often spent his holidays in D.C., hoping to get legislation passed before members of Congress went home for their breaks. And coming home without a victory was hard.

“What kept me going was the faces of all the people I met in the South. Some of these farmers had never left their county in their life,” he says. “I knew that they would never see justice.”